This blog, which recorded my three weeks as a part of the Ise and Japan Study Program from February 23 to March 13, 2015, is now inactive. Please feel free to peruse old posts and photos or click the above link to learn more about the program and its various activities!

All posts by Paula

Our final days in Ise

Our final two days in Ise were a whirlwind. We spent most of yesterday preparing for our presentations in the morning, and then headed to the university for final checks on our power points and last minute questions. We had our last lunch at the school cafeteria, where the workers were kind enough to send us off with some specially-made mochi cakes with sweet potatoes.

When we returned, the eleven of us had our final presentations in front of the volunteer students, professors, and a couple of representatives from Ise city. Since we were free to give talks on whatever we wanted, there was a great range, some of which included the special experiences we had at Ise, ways the city could help market itself to overseas tourists, and individual research. Personally, I gave a presentation on the connection between my research on artisan, courtier, and warrior networks and cast object production in the late medieval Ise province. I’m hoping to be able to come back and do more work in Ise in the future, so it was nice to be able to introduce the topic to students and professors, many of whom were not aware of this area of Ise’s premodern history.

When we returned, the eleven of us had our final presentations in front of the volunteer students, professors, and a couple of representatives from Ise city. Since we were free to give talks on whatever we wanted, there was a great range, some of which included the special experiences we had at Ise, ways the city could help market itself to overseas tourists, and individual research. Personally, I gave a presentation on the connection between my research on artisan, courtier, and warrior networks and cast object production in the late medieval Ise province. I’m hoping to be able to come back and do more work in Ise in the future, so it was nice to be able to introduce the topic to students and professors, many of whom were not aware of this area of Ise’s premodern history.

After a brief change of clothes at home, we then headed out to a wonderful Chinese restaurant with more professors and supporters of the program. As is typical at these types of going-away parties in Japan, we all gave speeches that allowed us to express our deep gratitude to everyone who made the program possible and extended such kindness to us. Everyone in the group was also glad that we had a chance to give a gift (a small [?] barrel of limited edition Ise sake) to Tamada-san, our coordinator who clearly went above and beyond the call to make sure our program went smoothly and we had everything we needed. He is magic.

After the party the eleven of us reconvened at the dorms to finish off the last of our alcohol and and snacks as well as pack for our departure.

In the morning, we returned to Kogakkan to hear kind goodbyes from the university president and many professors, as well as the sweet college student volunteers, most of whom cried to see us go. Everyone gave final words of thanks and goodbyes, we took photos, and gave out small gifts of candy from our own countries. Many of the students had also prepared nice little parting gifts.

In the morning, we returned to Kogakkan to hear kind goodbyes from the university president and many professors, as well as the sweet college student volunteers, most of whom cried to see us go. Everyone gave final words of thanks and goodbyes, we took photos, and gave out small gifts of candy from our own countries. Many of the students had also prepared nice little parting gifts.

A handful of students and Tamada-san saw us off at the train station, waving goodbye enthusiastically from the other side of the train station. After three weeks of intense studying, touring, and meeting new people, we are all exhausted, but so happy and honored to have had the experiences and made the acquaintances that we did. All of us feel such a depth of gratitude for the great efforts so many people went to on our behalfs, and are awed at the kindness we received. Though these three weeks are over, I don’t doubt that before too long we’ll all be seeing each other again somewhere in Japan.

I hope that those who have been following this blog enthusiastically embrace all that Japan, especially Ise, has to offer, and get the chance to share in it and share it with others in the future. Thanks for keeping up with me here in Ise and definitely take the time to experience it yourself!

Artisanal labor and the rebuilding of Ise shrines

Since tomorrow is our last day of the program and everyone is busy preparing their final presentations, today we only had one lecture (our last!), and the rest of our time we were free to wander about. For our lecture, were able to travel once again to the Outer Shrine (Geku) of Ise, where we were welcomed into the Engineering Office behind the scenes.

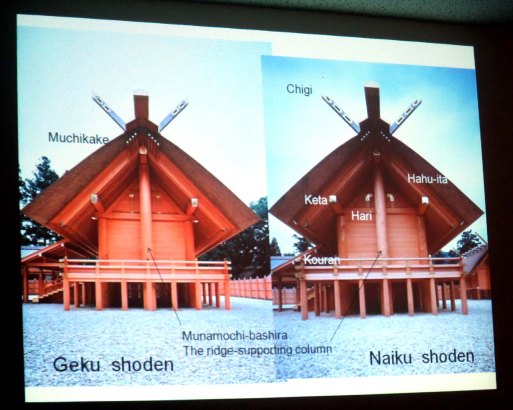

There, we were given an hour long lecture about the construction process for rebuilding the shrines every 20 years, including discussions of individual parts of the shrines and a comparison between the Inner and Outer Shrines’ main halls. There are small structural differences, as well as some small outer buildings that serve different purposes given the different function of each.

The area outside of the engineering office is used to store some of the lumber, particularly on the waters, and we were told about ceremonies involving the felling of trees for the process, as well as traditional ways of marking wood. Our guide explained the building process as well, noting that when working with the wood, gaps are left at joints so the lumber can shrink or expand with the weather without damaging the structural integrity of the buildings.

As always, I was struck less by the architectural plans themselves, and more by the actual people who build them. There is not a set group of people who work on the shrine reconstruction, but carpenters come from all over the country to participate in the de- and reconstruction of the shrines every twenty years. At the most, our lecturer told us, there are usually about sixty people who come to work on the building process, and they vary in age. He said that this year the youngest carpenters were in their thirties, which meant that they were not as skilled as many senior members, but that he looked forward to having them participate again in twenty years when their skills had increased over time. What’s more, their most senior members who participated last year were in their eighties, and enthusiastically wished to contribute to the project for the second or third time in their lives. At the end of the process, ten or so carpenters immediately return home, while some stay to help repair or rebuild other parts of the shrines in the complexes.

Though we were a little rushed for time at the end, our guide also explained the minute processes involved in collecting and preparing smaller hand-worked pieces for the shrines. For example, miscanthus is gathered from the fields of Kawaguchi-kaya mountain by women and brought to artisans to line up, cut, and thatch the roofs of the shrines when they’re fully erected, and metal work for the gold adornments takes careful attention to detail by artisanal masters of design.

I won’t go into a great deal of detail, since I have plenty of work ahead of me tonight, but after the lecture we were free to roam and finish up any shopping or work we had to do. As a personal goal, I finally got to go out and try Ise udon, which is an area specialty known for its strong soy sauce flavoring and thicker, softer noodles than usual. It was delicious! Back to presentation preparation for now, though. 🙂

A little taste of traditional tea ceremony

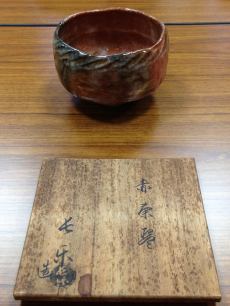

Today we were given a special lesson on tea and tea ceremony at the Kōgakkan memorial hall on campus that we briefly toured our first day here. The hall has a large open area next to two traditional tea rooms, the first being a small, private tea house and the second being a large one capable of fitting a large group for tours and lessons. Tables were set up for us to have a formal course in the beginning of the day, along with four large tables in the center filled with tea objects. A number of very old and valuable objects were included among them, though most everyone’s favorite was a beautiful tea bowl from the late Edo period (19th century). Many of the objects were in pristine condition only because the tea masters treasure the items so much and carefully maintain them.

We began with a lecture about the history of tea, going all the way back to 2,780 BC, when it is first believed that tea was recognized as a drink with medicinal properties, and broke down the meaning of words in ancient materials first used to described tea. Our lecturer, of the Urasenke tradition of tea ceremony, walked us through the introduction of tea to Japan. Although tea was drunk by priests and envoys that traveled to continent, is believed that the priest Saichō first brought tea seeds to Japan around 805 on his return from travel to China. After being introduced to and enjoyed by Emperor Saga (r. 806-809), tea became a popular luxury item among the nobility.

Our guide discussed the spread of tea and its waxing and waning in Japan along with contact with China, then discussed the different words used for tea around Asia, as well as different understandings and uses of the character 茶 for “tea.” He then spent some time explaining the elements of tea ceremony that involve serving food, and discussed what types of food (such as rice, miso broth, fish, etc.) were brought out and the specific order in which they appear in proper ceremonies. All in all, a full ceremony should take as much as four hours.

After a brief break for lunch, we returned to explore the tea rooms of the hall and the process of the ceremony itself. We had several guides, and Yamada-san, dressed in a beautiful kimono, explained the purification process before entering a tea room and explained the design of small tea houses. Even entering the small doors has a ritual element to it. Although people familiar with tea ceremony probably know this, the low positioning and small size of entrances in the traditional, small tea rooms are such that people who wear weapons must remove them, and despite high rank, any person who enters the room enters on an equal level, humbled as they crawl through the small opening. The small tea house in the memorial hall is actually an authentic one, built by an old shop in Kyoto about one hundred years ago, and moved to the memorial hall in Ise after it was built. Wow!

Tea ceremony is a very involved process, and our guides informed us that it takes decades to even learn the proper way of holding and turning a tea bowl or carrying a tray. During a simple tea ceremony such as that which we were introduced to, very small, sugary sweets are served before you drink to offset the bitterness of the green tea.

In the large tea room, were served by the students of tea ceremony who were assisting us, then we were each given trays of tea with the tea powder inside and instructed on how to whip the contents with a wooden whisk into a beautiful froth (although I admit I was not very good at this—it takes enormous strength of wrist!). It was a real treat to be able to hear about tea and tea houses from experts, as well as experience it firsthand. If someone ever offers you the chance to try tea ceremony yourself, definitely take it!

As usual, more pictures in the gallery!

Salt making and breaking in Oomiya and Ise on the sea

After our long weekend running about Kyoto send Nara, today’s schedule was on the light side. We had one lecture in the morning by Okano-sensei focusing on the towns of Oomiya. In the case of Oomiya, this town, which is actually an island, has a deep connection to the sea, and was originally known by the name Oojioyamiso 大塩屋御薗, the first three characters meaning literally “large salt shop.” From long ago this town was a central area for salt production. From around the mid-medieval period (c. 14th cen), Oomiya began appearing in records of Ise as a port town, and even in the famous fictional history Taiheki appears as a place of importance from which warriors could depart by ship to travel towards eastern Japan, a possibility largely due to its prominent salt production and trade. Though Taiheki is fictional, its description of Oomiya attests to its importance, enough to be included as a recognizable port of relevance in the tale. Okano-sensei believes that this exchange with the east was particularly prolific because areas to the northeast of Ise did not have good conditions for salt production, leading to the need to import from the more southern locations.

In 1498, an earthquake of 8.2 to 8.4 magnitude struck the entire Ise area, which in one day completely sank all the salt producing areas into the sea. Written about in detail in records of the time, over 5,000 people in Oomiya are said to have died, though hundreds more in neighboring areas also perished. One record even specifically states that over 100 salt-making houses connected to local shrines were destroyed all at once. This effectively eliminated the majority of salt production in the area, and led to places like Futami, which previously did not produce salt, to enter into the salt making business after the earthquake.

As a result, Oomiya was forced to find other means of survival as a town, and afterwards turned to ship building for its livelihood. The Portuguese missionary Luis Frois even wrote in the late 16th century that Oda Nobunaga had the people of Oomiya make him the largest ships in Japan, and that in his opinion they closely resembled those in Portugal. The ship business was especially lively for Oomiya into the 17th century.

In the afternoon, we went out to actually see much of Oomiya, and were given tours of a small marine museum as well as much of the old neighborhood of the area. There was a great deal of reconstruction after the majority of the older buildings were lost to bombings in WWII.

Our guides had prepared a special treat for us, which was a tour around the waters on a small wooden boat. They had even lined up the flags of the countries we all come from to hang on the ceiling. Our guide told us about industry in the area, including fishing and ship-making, and brought us to our next series of tour spots.

Due to sheer exhaustion, I won’t go into details of every place that we visited today, because we were on and off the bus at a variety of stops all over (and rather quickly due to rain). But some of the highlights included a small shrine where salt used to be offered to the kami before the 1498 earthquake, and a large shrine, the Hihomiyama Hachiman shrine, with an enormous and very old pine tree out front. The placard out front had information regarding the late 17th century on it, so I assume that like much of the grand displays of nature that you can see in Ise, it has a very long history.

Two other stops that were quite notable were a former headquarters for bugyōnin, a kind of government administrator in the Edo period, and a blacksmith’s workshop. Bugyōnin had a variety of responsibilities as government officials, and in Ise included managing the bakufu lands in the area, overseeing the shrine reconstruction processes, and maintaining security in the area. The headquarters included a lovely little museum with neat artifacts like Edo period bugyōnin clothing.

At the small blacksmith’s workshop, we were fortunate enough to see two smiths at work making nails and other small objects. Earlier in the day, we had guides at the bugyōnin headquarters explain on a map the many locations in the area where small workshops had been maintained, which was likely of great importance in an area where ship construction proliferated.

All in all, it was tiring but very informative day! Check out the gallery for more great pics.

Sacred sites and special sights in Kyoto

After a night in a hotel very close to Tōji temple, we began our day of touring in Kyoto there. Tōji is a very popular temple with a long history, connected to Shingon Buddhism. The temple was built in 796, two years after the capital was established in Kyoto, and is associated with Kōbō Daishi, popularly known as Kūkai, who founded Shingon Buddhism in Japan. Although it is not normally open to the public, from January 10 to March 18 of this year Tōji is allowing people to enter the bottom level of the pagoda to see the Buddhist statues and paintings inside. There are beautifully gold-gilded figures and paintings of famous priests on the walls. But naturally, photos were not allowed inside. The same goes for the other halls, which house positively enormous sculptures of Buddhist deities and guardians. The sheer number and size is amazing.

Although we were not at Tōji on the right day, there is a flea market that occurs on the temple grounds each month that is very well attended, and I got the chance to go and see some of the fabulous antiques sold there when I was an undergraduate. If you get the chance, I’d highly recommend going. As a side note, there some places of worship a little off the main route to Tōji that are a part of the complex, and I as I wandered out there I stumbled across a large cast bell (!) which was made in 1348 and donated by Ashikaga Takauji, the famous founder and first shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate.

We then moved on to Yasaka shrine, which was founded even earlier than Tōji, in 656. This shrine is located in the famous Gion district of Kyoto, and the 869 parading of mikoshi, a mobile palanquin that enshrines a deity, in order to put a stop to an epidemic in the city was the beginning of the well-known Gion matsuri, a central part of city life and Kyoto identity over the centuries. It is believed that the shokunin uta awase emaki (artisan poetry competition handscroll) paintings that showcase numerous artisanal workers in and around Kyoto was created around 1500 in part because of the revival of this festival made the presence of artisans in the capital particularly prominent in the cultural imaginaries of the courtiers who made the scroll.

We were guided through the temple with special access to the main hall by a former Kōgakkan University graduate who is now a priest at the shrine. He explained to us about the history of the shrine and showed us some of the remarkable pieces of art kept there, which include a painting of a rooster with cage lines included because it was painted so realistically it was believed it might leap out of the painting, and a Nanboku period (1333-1392) Buddhist statue which was kept at the shrine and survived the Meiji period forced separation of Buddhism and Shintō.

Also, we were lucky enough to catch a ceremony at the temple in which people of the city participate. Yasaka shrine is built atop of a sacred well that is still functional today, and once or twice a year people from the local shops come to the shrine to receive water from the well from the priests. A ceremony is conducted with the carrying of the sacred water and traditional gagaku music is played as they carry it off.

Our lunch time was free, so friends and I wandered through the streets of Kyoto until we found a soba restaurant, where I had incredibly delicious hot duck soba. Most of our goals for wandering the city inevitably involved eating. And the food in Kyoto (vanilla-maccha ice cream and maccha-an tayaki included) definitely did not disappoint.

Afterwards, we toured Kiyomizu temple, a temple founded 798 that sits high above the city. This is a major tourist thoroughfare, with winding streets loaded with shops full of souvenirs, tasty treats, and of course, tons of visitors. As you climb the mountain through a series of stone steps and enter the temple grounds, Kyoto begins to disappear beneath you. Despite the crowded nature of the temple (moreso than any site I think I’ve been to thus far), you’re able to enjoy paths curving along the mountain side that wrap around and give an excellent view of the large structures that make up the complex.

As a final look to the temple (our last stop of the day), I’ll show a picture below of the steep drop from the main platform. Jumping from the platform apparently has a very long tradition. As Wikipedia states:

The popular expression “to jump off the stage at Kiyomizu” is the Japanese equivalent of the English expression “to take the plunge”. This refers to an Edo period tradition that held that, if one were to survive a 13m jump from the stage, one’s wish would be granted. Two hundred thirty-four jumps were recorded in the Edo period and, of those, 85.4% survived. The practice is now prohibited.

More great things in the gallery!

A day in the ancient capital, Nara

Today we started bright and early, taking the express train from Isuzugawa station to Nara (with one transfer). It was a short trip, less than two hours, and put us right in the heart of the ancient capital. As some of you may know but others not, Nara was the seat of the ancient government from 710 to 794, and was also (not insignificantly) the center of Buddhist religious practice. The imperial capital was afterwards moved to Kyoto (Heian-kyo, thus giving the name Heian period to the years 794-1185) to divorce Buddhist leadership somewhat from political affairs. It is up for debate whether Nara is better known for its temples or the deer that roam free throughout the city begging for food.

We got straight to it, and began our tour at Kōfukuji, which features the Eastern Golden hall and the five-storied pagoda. Kōfukuji was originally established in the 7th century in Yamashina (present day Kyoto), then moved to Fujiwara-kyo, and finally relocated to Nara  in 710. The main statue of worship at the Eastern Golden Hall is the Yakushi Triad (left), a very famous set of statues. We didn’t get to see them, but anyone who has studied art history will probably recognize them if they get the chance. After a brief touring (with a very kind guide) around the front of the buildings, we had a chance to enter the Kōfukuji National Treasures museum, which is stocked full of incredible premodern pieces of Buddhist art from Nara area. Pictures were not allowed inside, but if you get the chance to go, I suggest you spend some extra time looking at Kamakura period (1185-1333) sculptures, which, in the case of monk portrait sculptures, took on a stunning realism, and in the case of demonic or Buddhist protector figures, took on a hyper realism with great bulging muscles and vivid energy in the lines. Both often started to use crystal or glassy for the eyes in these wooden sculptures, lending an eerie realism to them.

in 710. The main statue of worship at the Eastern Golden Hall is the Yakushi Triad (left), a very famous set of statues. We didn’t get to see them, but anyone who has studied art history will probably recognize them if they get the chance. After a brief touring (with a very kind guide) around the front of the buildings, we had a chance to enter the Kōfukuji National Treasures museum, which is stocked full of incredible premodern pieces of Buddhist art from Nara area. Pictures were not allowed inside, but if you get the chance to go, I suggest you spend some extra time looking at Kamakura period (1185-1333) sculptures, which, in the case of monk portrait sculptures, took on a stunning realism, and in the case of demonic or Buddhist protector figures, took on a hyper realism with great bulging muscles and vivid energy in the lines. Both often started to use crystal or glassy for the eyes in these wooden sculptures, lending an eerie realism to them.

After the museum, we took a scenic walk through some of the park areas in Nara on our way to lunch, which led us through a beautiful pond and pavilion section of the city. We were lucky that the rain held out in this early part of our tour. At lunch time, we headed to Tatsuya, an udon noodle restaurant, and had Takabatake udon, which was fantastic. Weirdly, although this entire trip we have been told that we have to try “Ise udon,” I believe this is the one udon we have yet to actually eat.

After lunch we headed to Kasuga shrine, a Shintō shrine in the midst of city so rich with Buddhist temples and influences. Originally established in 768, Kasuga shrine is the family shrine of the Fujiwara, a family intimately tied to (and prominently married into) the imperial family. Although there is a rich history to Kasuga shrine that I’m sure many would be glad to hear all about, here I’ll be a bit frivolous and show you this incredible tree close to the main hall that the shrine has literally been built around, with the tree sticking straight through the roof. Right next to it was another positively enormous tree that is said to be over 1,000 years old (see the gallery for a shot of it). There is also a wisteria tree in the front of the shrine thought to be 800 years old. Both trees apparently can be seen clearly in a handscroll painting from 1309, proving their advanced age.

The main feature of Kasuga shrine was a real treat for me, since I research metal casters. They are known for their stone and bronze lanterns, said to have over 3,000 stone lanterns lining the way up to the shrine and over 1,000 bronze lanterns within. Our guide, a priest at the shrine, told us that they have some lanterns that go back as far as the Heian period, but many date from the Muromachi (1336-1600) period. You can see the difference between the older lanterns that have oxidized to a green color and the fresh golden lanterns that are so shiny and bright.

In the past, these lanterns were lit up using oil, but today they use small candles instead. There is also a special hall in which they have dozens of these lanterns lit up and curtains drawn so that the full experience of their light can be felt. I must have taken 50% photos of lanterns today.

After Kasuga, we continued on and trekked across the city through the rain to Tōdaiji, one of the most famous temples in Nara. Founded in the early 8th century, Tōdaiji houses the world’s largest bronze statue of the Buddha, known as the Daibutsu (literally, “Large Buddha”). When you walk in and see the sheer size and height of the Daibutsu, and the temple itself, it is absolutely awe-inspiring. What’s more, the current state of the temple is not even the largest it once was. The Buddha Hall was burned down during the Genpei Wars in 1180, and then was burned again in 1567. If you look in the gallery, there are fantastic scale models on display to show what the different shapes and sizes of the hall were after each reconstruction. The present size of the hall is approximately 33% smaller than the original, yet is still among the largest wooden structures in the entire world.

The statues surrounding the Daibutsu are also incredible to see, some of which still retain the majority of the gold gilding they were created with (see below). Although I could bore everyone for some time with details about metal casting in premodern times, I’ll simply say here that the Tōdaiji metal casters who worked on the Daibutsu in Nara were among some of the most skilled and highly sought-after in their time. To be known as someone who descended from a “Tōdaiji” metal caster was an important recognition even centuries later.

Since the rain was coming down so hard, we decided to head to Kyoto rather than stay an extra hour. We checked into our hotel and had some time to relax before dinner, which was nice, since we’re all completely wiped from such a long two weeks and so much travel. Off for more adventures tomorrow, this time in Kyoto! There are a ton of great photos from today, so check them out!

Links between centers

Since many of us are still lagging on energy after a long and productive week of lectures and touring, today we had a lighter day in preparation for going out of town to Nara and Kyoto tomorrow. Today’s lectures also focused somewhat on the exchange that occurred between Ise and these two cities. We were once again treated to a lecture by the university president, Shimizu-sensei, whose specialty is Nara. Beginning with the idea that the culture of the capital is represented by the term miyabi (refinement or elegance), in contrast to which localities, which were represented by hinabi (rusticness), he noted that Ise, having its special relationship to the imperial court in the capital, was at the same time as being a locality far outside of the capital, also uniquely connected to it, and thus represented by the word pinabi (though I’m afraid I did not catch the nuance to Shimizu-sensei’s explanation). With the act of the ancient emperor Suijin sending his daughter to find a place to enshrine Amaterasu, and the inevitable selection of Ise, Ise’s special relationship to the central area of government was secured. At the same time, it represented the oneness of government and religious practice at the time.

This oneness was facilitated by the role of the emperor, who is considered to be a Shinto priest himself, and who conducted important rituals for the sake of the nation as a touchstone for kami like Amaterasu on earth. Enshrining and worshipping Amaterasu with various rituals (which Shimizu-sensei explained at length but I won’t go into in detail here) at Ise is thus inevitably connected to the emperor’s activities and presence in the capital, particularly through the performance of worship by his daughter, the priestess of Ise, who lived at Saiku and brought with her culture of the capital while serving as representative of the emperor. Many of the rituals performed by the emperor while he was in the capital were also performed at the same time in Ise. Some exceptions existed, however, such as Tanabata, which was celebrated in the capital but not in Ise.

Our second lecture focused more generally on the modern significance of matsuri and the notion of ritual worship of kami. Our professor spoke of ideas connected to matsuri such as a desire for purification/cleanliness extending back to mythic tales of the past and continuing today, with over 300,000 matsuri ritual celebrations in Japan per year. They are thus deeply embedded in daily life, and people make matsuri activities and visits to shrines an integral part of their life experiences through prayer and performance.

Kyoto was the focus of our afternoon lecture by Kamo-sensei, and we looked to two different connections as the main bridges between the Heian period capital of Kyoto and Ise. The first is the Saiō, the aforementioned female relative of the emperor (usually a daughter) who serves at Saiku as the priestess of Ise, though she actually only went to Ise itself from Saiku (set slightly apart from the shrine) three times a year. Who would serve as Saiō was typically decided soon after the enthronement of a new emperor.

The other bridge between the court in Kyoto and Ise was the Shiō 使王, an imperial messenger who was dispatched to Ise from the court three times a year as well. Although the tradition of a Saiō serving at Ise ended in the early to mid 14th century, the dispatching of an imperial messenger to Ise continued through the early modern (Edo) period. The major task of a shiō was to present heihaku, or offerings, often of cloth or other goods, for matsuri honoring the kami, especially Amaterasu. The task of offering heihaku can be seen in ancient texts as early as the 8th century. Ise had traditions particular to its shiō selection, in which the person serving was usually above fifth rank (quite esteemed) and was selected by a process of uranai, or divination. An entire organization specifically dedicated to divination long existed within the premodern court, and its practitioners (onmyōji) are even now extremely popular figures in various media.

Our classes ended early today and my trip to the library for research after it was not particularly remarkable, so I’ll end here. We’re off to Kyoto and Nara bright and early tomorrow!

Warriors, merchants, and tofu in old Ise

Our morning lectures began with Kanno-sensei, who proposed to speak with us on how Shinto and Bushidō are linked. He began with a discussion of how we understand warriors today versus their appearance in the premodern period, emphasizing that the word bushi for warrior did not exist for some time, and that the origins of warriors rest in their roles as farmers. Kanno-sensei explained that the first real attempt to define what a warrior was appeared in the Kamakura period in the form of a definition of gokenin, or house men in service to the bakufu (military government). In this definition, gokenin are recognized as those who develop their own land and protect it by their own means. Extending this role, a legend in the fudoki (ancient records of provincial culture, geography, and oral tradition) of Hitachi province tells the story of a warrior who faces off with a kami who objects to his opening of new land, after which the warrior promises to devote the land to the worship of kami. In this story, it is possible to see the early connections between warrior identity and Shinto practice. Kanno-sensei pointed out that Goseibai shikimoku, the earliest warrior set of laws from 1232, states in its first article that warriors have a responsibility to repair shrines and properly perform Shinto rites.

Although Kanno-sensei did not get a chance to get through all of his lecture, I was glad to see that he spent some time trying to explain the problematic nature of thinking about bushidō as an ancient or medieval concept, as it was a word that did not exist even partially in the form we understand it in popular knowledge today until after into the Edo and Meiji periods (17th to 19th cen). He emphasized that self-conscious use of the word bushi and bushidō emerged in the Edo period period, but was cultivated carefully in the Meiji period to suit the image of Japan that Japanese wished to project to the Western world during this time of extensive international interaction. The harsh, bloody, and self-serving elements of warriors of the past were whitewashed to meet a moralistic image comparable to the idealized medieval knight of Europe, and the warrior ideal was ossified. While it would have been nice to hear more about the connections between warriors and the court in the late medieval and rarely modern periods to gain a better sense of later connections between warriors and Shinto practice, I was glad that Kanno-sensei took the time to elaborate this part of warrior history. The fetishization of bushido and feudalism as applicable terms and ideas in premodern Japan is a personal pet peeve. Anyone interested on the subject in Japanese historical research should consult work on bushidō by Thomas Conlan, John Hall, Thomas Keirstead.

Our second set off lectures were led by Chieda-sensei, who gave us extensive background on economic production in Ise, particularly in the Kawasaki furuichi area, in preparation for our afternoon tours. In premodern times, the Ise area existed as an important point for maritime trade to the eastern part of Japan, and into the sixteenth century, with the reconstruction of the Ise shrine, there was a great deal of exchange along the Setagaya River and the Kawasaki area along it was well-placed to be an area where merchants could settle, markets be established, and lodgings provided for various travelers and people in commerce. A number of important and active markets existed in the area, and major items of production include fish products, rice, and sake.

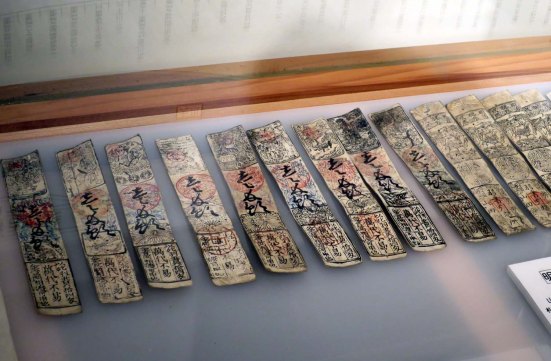

Chieda-sensei showed us some amazing old documents that contained lists of major families in the commercial businesses of the Kawasaki area, and also introduced us to hagaki 羽書, a type of paper money issued within Ise that is considered to be perhaps the first true form of paper money in circulation in Japan. These first began around 1610 with the issuing of Yamada hagaki in the Yamada area of Ise, and despite bakufu attempts to stop it, continued to be used. It even had special stamps that helped prevent forgery attempts, attesting to its value in practical use.

In the afternoon, we had the chance to go to Kawasaki Furuichi and see this commercial area firsthand. We toured through a number of museums and old shops as Chieda-sensei told us what buildings were authentic, such as buildings that have gone out of use today but used to be used widely for cider production. One museum we did go to actually still produces the local cider which was once highly popular in Ise, and they suggested we try some to get a real taste of the Meiji period (the shop has been producing cider since 1910).

We were invited into an old pottery shop which has also stood the test of time, and were able to travel deep into the back of the shop along the old rail tracks that were used to carry pottery to the front of the store. Many of the objects in the store originate from its original time, surviving from the Edo period. We were able to enter the attic and see stores and stores of old objects from bygone times, piled up and gathering dust. It was incredible just to imagine what sort of treasures must have been buried inside.

We also were granted special access to an inn from the mid-Edo period (late 18th century) that still functions today. It has one of the absolute best views of the city, as it sits atop a hill overlooking the mountains.

Aside from the traditional architecture preserved in the expansive residence, it also houses many different treasures surviving over the centuries. Although photographs were not allowed, one of these objects was a hanging scroll which had (surprisingly) English cursive writing awkwardly presented down from top to bottom. It read:

In the house of Asa Kichu we have found good accommodation and received attention

Henry Marsham

George W. Buchanan

January 5th, 1882

WOW! I have no idea who they are, and am certainly too tired to look it up now, but it’s amazing that such people passed through that very inn some 130 years ago, leaving behind a trace of themselves that’s kept to this day.

Although we visited many other places, our final stop on the walking tour was a togiya, or sharpener’s shop. Sword and knife sharpeners have a long history as artisans in Japan, and although the man running the shop is not from an extended family of sharpeners, he quit his life as a salaryman to take up the craft with a passion. He demonstrated to us how knives are sharpened and smoothed, and showed us how, with disturbing ease, one of his knives can cut through several layers of terry cloth or paper as if it were nothing at all.

In the evening, we went to Tōfuya, a tofu specialty restaurant where we were served a many-course meal of various tofu-related dishes. It was absolutely delicious, and I encourage you to look on my photo gallery with great envy. I would write more about Kawasaki or dinner, but we had a terribly long day, and I hope everyone will get the chance to look into these fabulous locations on their own too! Check out the pictures for Day 12 at the bottom of the gallery section!

Itinerant priests, wards against evil, and hidden history

Starting once again with lectures by Okada-sensei, we had a combination of two talks in the morning and touring experiences in the afternoon. The theme of the morning was customs of Ise, and we began with shinsei kindan 私弊禁断, the custom from ancient times that only the emperor was allowed to worship at Ise shrine as a representative of the entire country. This of course gradually changed, and it is known that during the Genpei wars in the 12th century Minamoto Yoritomo prayed for the defeat of the Taira at Ise, and since then many warriors came to worship there.

We then talked of onshi 御師, people who had various duties at the site of the shrine itself, such as providing food or labor, and starting in the end of the Heian period began to travel around the country. Oftentimes these figures would live under the protection of influential figures such as Sengoku daimyo and were ranked courtiers. In the Edo period, onshi continued to be prolific itinerant priests who traveled the country spreading the beliefs of Ise and distributing amulets or other Ise-related tokens to believers. Okada-sensei told us that about 80-90% of Edo people believed that if they didn’t go to Ise at least once in their lives they were no better than animals, suggesting the persistence and reach of the faith in Ise beliefs.

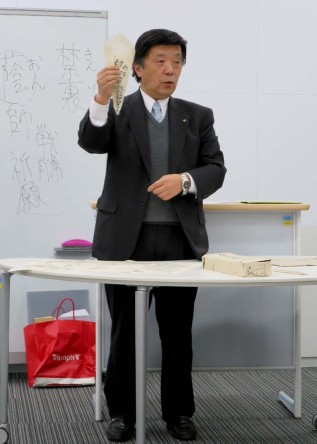

Onshi would distribute charms and talismans such as ofuda that would be used to ward off evil and purify a home or room. Here Okada-sensei shows us one particular type, a sword talisman of purification (made of paper, in the form of a sword) from the Edo period. These were meant to be used only once, although other types of purification charms, some able to be used multiple times, also existed. Onshi also distributed white power makeup as omiyage for women, who would become sunburned from their travels. It was made with mercury, which was dangerous to their health and often killed them, though people did not know at the time. Onshi also took medicine when they spread the faith and distributed it when they used prayers and medicine as a combined healing method. In the beginning of the Meiji period (1870) the onshi were abolished.

Our second lecture, also by an Okada but a different Okada-sensei, focused on customs starting with shimenawa 注連縄, or rice straw ropes. There are a number of types of these ropes that are used for different occasions, often at spiritual sites to mark their sacred nature, but some are used on specific days for specific purposes. Often, if you visit Japan around the new year, you will see such ropes affixed to the front of homes and businesses in order to ward off bad spirits and invite in good ones. These are typically taken down after a few days, but in Ise they are hung all-year round because of the strong spiritual presence of the shrine and the goddess Amaterasu.

There are specific reasons for certain parts of these rope hangings, such as the use of holly to ward off ogres (because it hurts their eyes), or mikan (a type of orange) to bring longevity to your family. There is a tale behind the kind rope hanging pictured here. In this tale, a poor traveler is on the road by himself and has come a very long way. When he grows too weary to travel he stops at a large and fancy inn and begs to be given shelter for one night, but the greedy and snobby inn keeper refuses him for looking poor and dirty. The traveler then stops at the home of a poor farmer named Somin Shōrai who says that he doesn’t have much, but offers his humble residence and what meager food he has. The traveler, who is in fact a god in disguise, gives the charitable Somin a magic jewel that will bring good fortune to someone with a good heart, and eventually the humble farmer becomes the richest man in the town, but is still a thoughtful person who helps others. The straw ropes hanging in doorways are thus a way to invite in travelers and gods of fortune while protecting a house. There are many other versions of this story across Japan (including ones in which the charm Somin receives is the straw hanging, which protects his family from disease).

Our afternoon touring, much like yesterday’s visit to the salt field, focused on traditional places of production as well as old architectural sites. We took a tour of Kōjiya, a shop which makes soy sauce and miso paste. Their business was founded in 1817. Our first stop there was the ramen shop they run next door, where we had an absolutely delicious miso-based ramen for lunch. After that, we got to meet the owner of the Kōjiya, who is the seventh generation to inherit the business. We were given a tour of the large wooden house attached to the shop and work area, which was built (themselves) out of wood 120 years ago and is still actively a home and place for entertainment today. They have a number of prized possessions in the form of calligraphy and paintings that have been passed down through the years, including an amazing folding screen painting of scenes from Heike monogatari that was they suppose was painted in the Edo period.

After getting to see where and how the miso and soy sauce was made, the owner talked a bit about his family lineage. Chieda-sensei, a medieval and early modern economic historian, was on the tour with us, and after the realization that this family was a branch of another merchant family Chieda-sensei has been researching, the owner casually offered to bring out some old Edo period documents on his family lineage that the family kept in their possession. It was amazing to see what coincidental connections were made!

After we finished at the shop, Chieda-sensei took us on a walking tour of this area of the city, showing us the main road that leads directly to the Outer Shrine and used to be a main premodern thoroughfare for merchants and travelers to stay. As he guided us along the streets, he showed us what areas were market sites in the past for trade and exchange, and paused to show us particularly interesting attractions that still remain today, such as the storefront where mankintan, a famous cure-all medicine, was sold to pilgrims in the Edo period.

The absolute treat of the day, however, was getting to visit the Maruoka manor, which is a residence now turned part-museum owned by the Maruoka family, a continuing lineage of the above-mentioned onshi from the seventeenth century. The seventeenth century! The house itself was built in Keiō 2 (1866), two years before the Meiji period began. Much of the house is in disrepair and bears its original wooden structure. On entering you’re struck by the tilting beams, damaged walls, and uneven floors, but they add so much to the weight of the history behind them. Maruoka-san, the owner, is the 18th generation in his onshi line (though as I mentioned before, onshi were abolished in the Meiji period).

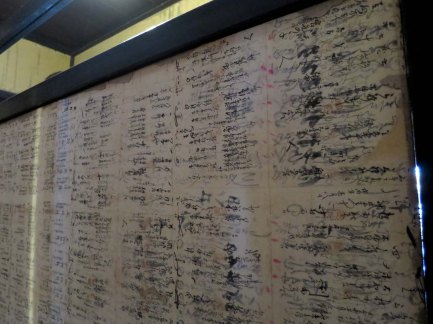

While at the residence, we were able to see rooms that had been just as they were for 150 years. But the most fascinating part was getting to see a real-life example of how historical records are accidentally preserved. On the back of a painting (see above) also from 1866, you could see that the painting was reinforced with a backing made of recycled paper (probably, the owner informed me, lists of important customers who came to his family for their services). This was a common practice in premodern Japan because of the high cost of paper. Many records not considered “important” at the time were used to stuff walls for insulation, mend doors or walls, or create backing for pieces of art. There is a special word for documents found on the reverse of other documents, paintings, etc: shihai monjo 紙背文書.

In cleaning up his family’s manor, Maruoka-san had found a cache of old documents pertaining to onshi and his family’s history. He showed us places where people in the early modern period had plastered their poems after a poetry party directly onto the wall, as well as the backs of doors that he had meant to repair, only to discover the entire backing beneath the paper was covered in sheets of recycled paper from the Edo period. Notice that behind the door where the poems are plastered, there are also MORE documents peeking out from beneath! Maruoka-san told us that he had found documents dating as far back as the sixteenth (!) century in his home. He even had an original set of printing tools for printing the ofuda we saw in class earlier!

Unfortunately, the city has not made it a priority, or perhaps even a mild interest, to preserve the incredible history found in the Maruoka residence. All of the renovations being done have been done out of pocket by the owner, who desperately wants to keep this treasured piece of his family’s history alive. It stands as a kind of monument out of time, the last of its kind in the Ise area, attesting to the deep and varied history of people who made the spread of Ise faith possible across Japan. If anyone is ever in Ise, I highly suggest you look into the opportunity to see this residence, and if anyone you know has an interest in keeping historical buildings like this safe, by all means let them know the Maruoka residence exists and needs to keep doing so! You can support them on their facebook here and help raise awareness of the residence. More fantastic photos in the gallery section!